Meet the educator-activists turning the tide on Mandarin hegemony to nurture a new generation of Taiwanese speakers and storytellers.

Founded in 2024, Keng-lâm Su-iⁿ (The Mosei Academy of Taiwanese Language and Literacy) has quickly become a dynamic and influential forces in Tâi-gí (Taiwanese) language revival. Rooted in a pragmatic praxis, the collective’s mission is simple yet profound: to make Tâi-gí a living, thriving language for everyday life, across generations and borders. From offering entry-level to advanced literacy classes, to hosting book clubs, creative writing workshops, and monthly community gatherings called Chhêng-á-kha, Keng-lâm Su-iⁿ creates spaces where speaking, reading, and dreaming in Tâi-gí feels both natural and necessary. In just its first year, the group published the first Tâi-gí textbook designed for English-speaking children in the U.S., filling a long-standing gap in teaching resources. Today, they are extending their reach even further, producing a documentary on Tân Lûi, one of Taiwan’s most prolific authors.

We were pleased to interview their leadership team, whose diverse life stories reflect the richness of Taiwan’s own history and diaspora. Tīⁿ Têng-têng, a heritage speaker, rediscovered her mother tongue in her forties, reclaiming Tâi-gí as a source of belonging and empowerment. Lûi Bêng-hàn, an engineer and steadfast advocate for Taiwan independence, lives his daily life through Tâi-gí as both a language and a practice of freedom. Hô Phè-chin, who immigrated to the U.S. at age fifteen after training as an engineer, carries forward her father’s enduring instructions: to preserve Tâi-gí and to uphold the cause of Taiwanese independence. And Ong Úi-pek, a tech lawyer descended from Taiwan’s post-war Chinese diaspora, brings to the collective an ongoing pursuit of Taiwanese identity—political, cultural, and linguistic.

Together, the collective embodies the many pathways that lead to Tâi-gí, and the conviction that language is inseparable from the struggle for identity, memory, and self-determination.

The History of Pe̍h-ōe-jī:

Q: Pe̍h-ōe-jī has a long history, with its roots going back over 150 years, predating the normalization of Mandarin in Taiwan. Could you share some insights into the origins of the system and its role in documenting Tâi-gí, as well as its impact in the literacy and education of Taiwanese people?

A: [Lûi Bêng-hàn] Thoân-kàu-sū tī 1830 nî-tāi kàu Tang-lâm-a tú-tio̍h kóng Hok-kiàn-ōe ê Tn̂g-lâng, tō siūⁿ beh siá in ê ōe. Kàu Chheng-kok ún-chún Se-kok lâng khì soan-kàu, chiu chiap-sòa teh iōng, chóng–sī iáu bōe ū kò͘-tēng ê hêng-sek. Bí-kok lâng John Van Nest Talmage sī gí-giân-ha̍k chhut-sin, tī Ē-mn̂g khòaⁿ tâng-kang teh siá, chiū chiàu gí-giân-ha̍k ê lí-lō͘ lâi chéng-lí chè-tēng kui-kí, tī 1852 chhut-pán Tn̂g-ōe Hoan-jī Chho͘-ha̍k chò Pe̍h-ōe-jī ê kàu-kho-su. Ba̍k-kim teh iōng ê Pe̍h-ōe-jī ū sió-khóa kái, chóng-sī bô tōa cheng-chha.

When missionaries encountered Hokkien-speaking communities in Malaysia during the 1830s, they sought to write in the local language. The writing system they developed—while showing slight variations from parish to parish—continued to be used in China once the Qing Empire allowed Western missionary work. When American linguist John Van Nest Talmage arrived in Amoy, he found his colleagues already writing in that system. Drawing on his linguistic expertise, Talmage refined it with more logical and consistent orthographic rules. In 1852, he published Tn̂g-oē Hoan-jī Chho͘-ha̍k as a textbook for learning Pe̍h-ōe-jī. While today’s Pe̍h-ōe-jī has evolved slightly to further fit the uniqueness of Tâi-gí, it remains quite close to Talmage’s version.

Lán nā hoan-thâu khòaⁿ Au-chiu, 16 sè-kí hit-chūn lóng iáu teh siá Lia̍p-teng-ōe. Niû Tn̄g ê Principia mā bô hoat-tō͘ kō͘ Eng-gí siá. Tang-a mā sī án-ne. Tiong-kok-ōe ê su-siá tī 1920 nî-tāi chiah khai-sí hoat-tián, chìn-chêng nā beh siá lóng sī siá Hàn-bûn. Tâi-oân-lâng chin hó-miā ū kàu-hōe lâi kà lán siá Tâi-gí, su-siá ê thoân-thóng pí Tiong-kok ōe khah chá 40 tang khí-kó͘, chhin-chhiūⁿ 1886 nî thâu 1 phiⁿ Tâi-gí siáu-soat Ji̍t-pún ê Koài-sū tō sī kiàn-chèng.

Now let’s turn to Europe. In the 16th century, Europeans were still primarily writing in Latin rather than in their spoken vernaculars. Even Isaac Newton, when writing his Principia, could not rely on written English. A similar situation existed in East Asia: written vernacular Chinese only began to take shape around 1920. Prior to that, the dominant written form was classical Chinese (Hàn-bûn), which bore little resemblance to how people actually spoke. By contrast, the Taiwanese were fortunate to have the Church’s guidance in writing vernacular Tâi-gí. In fact, the written Tâi-gí tradition predates written vernacular Chinese by about 40 years. For instance, the first Tâi-gí fiction, Ji̍t-pún ê Koài-sū (“Oddity in Japan”), was published in 1886.

Sui-bóng Pe̍h-ōe-jī sī kàu-hōe soan-kàu ê ke-si, sè-sio̍k ê lâng liâm-piⁿ tì-kak tio̍h i ū tōa lī-ek. Chú-iàu chhú i khoài o̍h, thang kín-kín sàu-tû chhiⁿ-mî-gû. Chhiūⁿ Chhòa Pôe-hóe tō chīn-la̍t teh sak Pe̍h-ōe-jī su-siá. Lîm Hiàn-tông ê khan-chhiú Iûⁿ Chúi-sim mā lâu chin-chōe Pe̍h-ōe-jī siá ê ji̍t-kì. Tâi-oân tī 1940 nî-tai liōng-tāi-iok ū 20-bān lâng ē-hiáu Pe̍h-ōe-jī.

Although Pe̍h-ōe-jī originated as a missionary tool, it quickly gained wider secular relevance. People outside the Church saw its potential—especially how easy it was to learn, offering a fast path to eliminate illiteracy. One prominent advocate was Chhòa Pôe-hóe, who devoted himself to promoting literacy through Pe̍h-ōe-jī. Another was Iûⁿ Chúi-sim, the spouse of renowned politician Lîm Hiàn-tông, who left behind numerous diaries written in the script. By the 1940s, it’s estimated that around 200,000 people in Taiwan had learned to use Pe̍h-ōe-jī.

Tī 1900 nî-tāi, bat Hàn-bûn ê lâng chin chió, nā chún bat, mā bô thang óa-khò Hàn-bûn lâi khip-siu hiān-tāi-hòa ê tì-sek. Chóng–sī kàu-hōe ta̍k kò goe̍h chhut-pán ê Tâi-lâm Kàu-hōe Pò, lōe-iông ū sin-bûn, kho-ha̍k, kang-thêng, chhòng-chok bûn-ha̍k kap hoan-e̍k bûn-ha̍k, lán ē-sái kóng, 1-ê tòa tī chng-kha, ta̍k kò goe̍h khòaⁿ kàu-hōe-pò ê chò-sit-lâng, i ê tì-sek kiám-chhái iâⁿ-kòe kà Hàn-o̍h-á ê sian-siⁿ.

In the early 20th century, very few people could read classical Chinese. And even for those who could, it wasn’t a practical medium for accessing modern knowledge. In contrast, the Church published a monthly newspaper, Tâi-lâm Kàu-hōe Pò, entirely in Pe̍h-ōe-jī. It featured news, science, engineering, original literature, and translations. One could even argue that a rural farmer who read Kàu-hōe Pò regularly might have been more knowledgeable than a traditional tutor (Hàn-o̍h-á-sian) trained in classical texts.

Khiā tī kin-á-ji̍t lâi khòaⁿ, ka-chài ū Pe̍h-ōe-jī kā kòe-khì Tâi-gí ê gí-im oân-chéng kì-lio̍k tī hia. Nā chún-kóng hit-chūn ê lâng sī iōng sì-kak-jī teh siá Tâi-gí, lán beh kā Tâi-gí o̍h–tńg-lâi tiāⁿ-tio̍h ē tú-tio̍h tōa khùn-lân.

Looking back today, we’re fortunate that Pe̍h-ōe-jī enabled precise documentation of pre-WWII Tâi-gí pronunciation. If people had chosen to use Chinese characters (Hàn-jī) instead, it would be far more difficult for us to learn authentic Tâi-gí today.

Reviving Taigi:

Q: What is the significance of reviving Tâi-gí, not just as a spoken language but as a cultural and historical marker for the Taiwanese diaspora?

A: [Tīⁿ Têng-têng] Language is a core element of cultural identity.

The sad part is, after two or three generations of Republic of China colonial education, many Taiwanese have gradually forgotten—or don’t even know—that before the ROC came to Taiwan, Taiwanese (Taigi) was the lingua franca, spoken by over 80% of the population.

Nowadays, many Taiwanese feel that the differences between Taiwanese Mandarin and Chinese Mandarin are important. They are sensitive about people using “支語” (Terms that come from China) or say “zhuyin” is a unique feature of Taiwan, part of our cultural heritage. But they don’t often think deeper: What is the mother tongue of Taiwanese people? Why did Taiwanese people start speaking Mandarin in the first place? Should our cultural identity be rooted in Taiwanese Mandarin or in Taiwanese (Taigi) and other Taiwanese languages?

When overseas Taiwanese search for our roots, we shouldn’t forget to understand Taiwan’s history—to find our true roots, not the ones instilled by colonial education.

Q: Could you speak about the intergenerational impact of Tâi-gí’s decline and how the preservation of the language can help heal cultural disconnections in both Taiwan and among overseas Taiwanese communities?

A: [Lûi Bêng-hàn] Góa chhin-sin ê keng-giām, chū góa kóng Tâi-gí í-lâi, hâm pē-bú kap A-kong lóng pìⁿ chò khah ū ōe kóng.

Let me draw from my own experience. Ever since I began speaking exclusively in Tâi-gí some 20 years ago, I’ve noticed a significant change. Communication between me and my parents or my grandfather has become much deeper and more meaningful than it ever was during the years when I primarily spoke Mandarin.

Siàu-liân-lâng m̄ kóng Tâi-gí, lán kiám-chhái m̄-thang kòe-siàu in. Lāu-tōa-lâng hō͘-siong kóng Tâi-gí teh khai-káng, liâm-piⁿ sun lâi, soah oa̍t-thâu kap sun kóng Chi-ná-ōe. Chit-khoán oa̍t-thâu-pīⁿ sī chin sù-siông. Lāu-tōa-lâng sòe-hàn bô o̍h Chi-ná-ōe, chu-jiân kóng Chi-ná-ōe ū Tâi-gí khiuⁿ. Sī-sòe siū si̍t-bîn kàu-iok tōa-hàn, lóng o̍h ē-hiáu kî-sī kóng Tâi-gí khiuⁿ ê Chi-ná-ōe, bōe-chēng si̍t-sāi hit-ê lâng, tāi-seng kám-kak in bô chúi-chún.

Fewer and fewer young people speak Tâi-gí today. But perhaps we shouldn’t be too quick to place the blame on the younger generation. A common scene plays out far too often in Taiwanese communities: elders chat among themselves in Tâi-gí, but the moment their grandchildren appear, they switch to Mandarin talking to the young ones. The older generation did not grow up speaking Mandarin, so when they speak it, their Tâi-gí accent is unmistakable. Meanwhile, younger generations—educated under a colonial system—have been taught to associate that accent with ignorance or backwardness. As a result, they often judge their elders unfairly before even getting to know them.

Chū án-ne, siang hong-bīn beh kóng-ōe, tiāⁿ-tio̍h ài ū 1 pêng hi-seng, kóng ka-tī bô se̍k-chhiú ê ōe-gí, sòa hō͘ tùi-hong khòaⁿ-khin.

As such, when two generations attempt to converse, it always ends up with one side having to make the sacrifice of using an unfluent language, while being looked down upon by the other side.

Koh, chêng si̍t-bîn ê Tâi-oân bûn-hòa tiāⁿ-tio̍h ài iōng Tâi-gí lâi kóng. A Tâi-gí hiān-tāi-hòa ê pō͘-hūn lóng sit-lo̍h, it-poaⁿ ê lāu-tōa-lâng mā kóng bô-lō͘-lâi. Tì-kàu lāu-tōa-lâng kap siàu-liân-lâng oh tit chhōe-tio̍h kiōng-tông ê ōe-tê.

Further, the pre-colonial Taiwanese culture is embedded in Tâi-gí. Meanwhile, due to colonization, we’ve been denied the chance to modernize Tâi-gí — to develop the vocabulary needed for new ideas, technologies, and cultural changes. This is not something the average grandpas can achieve on their own. It requires the support of both the state and the intellectual community. As a result, it becomes increasingly difficult for different generations to find shared topics of conversation.

M̄-chiah lán tī Tâi-bí-lâng ê chū-hōe, lāu-tōa-lâng hâm siàu-liân-lâng lóng bô kau-chhap.

In my opinion, this is one of the main reasons why, in many Taiwanese American events, the older generation and the younger generation hardly have any interactions.

Khó-kiàn Tâi-gí ài ho̍k-chín, hiān-tāi-hòa, thang kóng bān-hāng-mi̍h, chò lán seng-oa̍h ê gí-giân, án-ne chiah ē ū chéng-thé Tâi-oân-lâng ê jīn-tông, chiâⁿ chò oân-chéng ê cho̍k-kûn.

That’s why the revitalization of Tâi-gí depends not just on preserving it, but on modernizing it. We must (re)gain the ability to use Tâi-gí to talk about anything and everything—to live our personal, social, and professional lives through the language. Only then can we fully embody a Taiwanese identity, and truly become a complete Taiwanese nation.

Q: What current efforts in Taiwan are being made to revive Tâi-gí, and how do these efforts reflect the changing cultural attitudes toward the language? What excites you most about the current wave of language activism? What concerns you?

A: [Úi-pek] Ever since the passage of the Development of National Languages Act (國家語言發展法) in 2018, and the subsequent establishment of the Tâi-gí Channel of the Public Television Service (公視台語台 / Kong-sī Tâi-gí-tâi), Taiwan has seen a steady uptick and reimagination of Tâi-gí usage, as well as a new generation of Tâi-gí content creators. Thanks to celebrity Tâi-gí users such as Jensen Huang, in recent years speaking Tâi-gí has even become something that is trendy and cool, particularly amongst the younger generation, which is in sharp contrast to the decades of diminishing and belittling during the postwar, Mandarin-speaking, colonial authoritarian KMT rule.

We see a rapid growth in Tâi-gí content creation, ranging from music, literature, movies, dramas, podcasts and YouTube videos. In music, styles are modern and diversified; in writings, great care is taken to ensure correct usage of Tâi-bûn or Taiwanese scripts; in theatrical productions, people paid close attention to historical accuracy in language themes. The common stereotype in the past (a falsehood deliberately nurtured by the colonial regime) that Tâi-gí is a dialect of the Chinese language, not a language of its own right, has been gradually debunked. More people came to the realization that Tâi-gí is an integral part of Taiwanese identity.

It is particularly encouraging to see that there is a small group of young parents who make the conscious decision to, from childbirth, speak Tâi-gí as the first language to the next generation so that Tâi-gí will become their mother tongue. This is so precious in an almost exclusively Mandarin-speaking Taiwanese society nowadays.

And it is exactly because of such harsh reality, these Tâi-gí families face stark challenges. The number of Tâi-gí families is far short of critical mass. Learning resources are overwhelmingly in Mandarin, and too few are in Tâi-gí. The most frustrating part is, once a Tâi-gí kid reaches school age and enters social life, what awaits them is an exclusive Mandarin speaking environment, from teacher, peers, lectures, to learning materials. Their surroundings will very soon shape them into a Chinese-speaking and Chinese-thinking person (or simply, a Chinese); their knowledge intake and worldview building can only be through the tool of Chinese language.

This is why it is so important that, at this juncture, we start thinking about the possibility of a Tâi-gí school system. Not just an hour per week Tâi-gí class as one of many curricula in a Mandarin school system, but a school system, from elementary school to college, that teaches, learns, reads, writes, and really lives a campus life using Tâi-gí as the only working language. This may sound like a fairytale in modern day Taiwan, but it is not without precedent in other parts of the world. Look not too far at the example of Welsh language revitalization. In a predominantly English speaking country, the Welsh people successfully established a Welsh school system, which allows their younger generation to learn in their native tongue, eventually “becoming Welsh”.

The good news is that Taiwan will soon welcome its first Tâi-gí experimental elementary school in Táⁿ-káu, Pak-niá Kok-sió (北嶺國小). This is a small step on the road of Tâi-gí revitalization, but nonetheless in the right direction.

On teaching Taigi:

Q: We’ve previously published a wonderful reflection from a student who took Taigi classes through the TAC’s online course catalog, in which she wrote, “For many, the desire to study Taiwanese stems from a longing to be able to communicate across generations and connect with relatives or grandparents on a deeper level. Our learning thus creates space for an exchange: the gift of relating to another in their heart language, and in return, becoming acquainted with a facet of their being that defies translation.”

What are your observations from the other side of that experience, as the educator facilitating such connections? What excites you most about this cohort of students and what brings them to these classes?

A: [Hô Phè-chin] As many young Taiwanese Americans trace their family roots, they often discover a language disconnect between their generation and the older ones, a gap they are eager to bridge. While Mandarin is now the dominant language in Taiwan due to complex political and historical reasons and boasts far more learning resources, it is not the “heart language” for many families. Even if parents or grandparents speak Mandarin fluently or semi-fluently, it is often Taigi (or another local language in Taiwan) that holds deeper emotional resonance. This desire to connect more meaningfully with their families through Taigi is what draws most students to our classes. As passionate Taigi educators, nothing excites us more than hearing students share stories about speaking or practicing Taigi with their loved ones, and how much joy and bonding those moments brought to both generations.

On Taigi: Fluency Unlocked:

Q: You note that this book was consciously designed with a “conversation-based, graphic-aided, intuitive learning experience, particularly suitable for preschool audiences, (but equally effective for other age groups and even adults).” How did you balance the need for simplicity in teaching Tâi-gí to children while also ensuring the depth and complexity adult learners would need to effectively and fluently communicate?

A: [Lûi Bêng-hàn] M̄-thang khòaⁿ goán chi̍t-má án-ne Tâi-gí kóng kah sià-sià-kiò, khah-chá goán mā bô chin gâu kóng. Án-ne pòaⁿ-lō͘ khioh Tâi-gí tńg–lâi ê lâng sī chin phó͘-phiàn. Gún hoat-hiān chin chōe lâng koat-sim beh kap gín-á kóng Tâi-gí, chiah hâm gín-á tâng-chê ha̍k-si̍p, chò-hóe chìn-pō͘. Chit-pún chheh tú-tú thang chò lán kiōng-tông ha̍k-si̍p ê khí-ki.

When you hear us speak Tâi-gí fluently today, it’s easy to assume we’ve always been this way. But that’s far from the truth. Like many Tâi-gí activists who only returned to the language in adulthood, we started off stumbling—stuttering, lacking vocabulary, unsure of grammar. Over time, we realized that for many of us, the motivation to reclaim Tâi-gí came from the desire to speak it with our children. That turned the process into one of learning alongside them—growing together, word by word, phrase by phrase. This book is meant to be the starting point for that very journey.

Nā oân-choân bē-hiáu kóng ê tōa-lâng, i ê thêng-tō͘ kiám-chhái tō hâm gín-á bô koh-iūⁿ. Nā sió-khóa ē-hiáu ê tōa-lâng, goán phó͘-phiàn khòaⁿ-tio̍h in ê Tâi-gí choân-choân Tiong-ok-ōe ê kù-hoat kap sû-lūi. Khòaⁿ lán khò-pún Te 1 khò sio-chioh-mn̄g ê gí-sû, goán kan-taⁿ kà “chia̍h-pá–bòe.” Nā gín-á chū-jiân tō án-ne o̍h–khí-lâi, bōe ke mn̄g. Nā tōa-lâng, kiám-chhái ē mn̄g kóng, nah-ē m̄-sí “lí hó?” Án-ne sian-siⁿ tō thang ké-soeh kî-tiong ê mê-kak, koh pó͘-chhiong pa̍t-kù iā-kú-káⁿ.

For adults who can barely speak Tâi-gí, their learning approach often isn’t far from a child’s. And even for adults who do speak some Tâi-gí, their speech is frequently shaped—if not distorted—by Mandarin grammar and vocabulary. Take Lesson 1 of this book, which covers greetings. We teach the phrase “chia̍h-pá–bòe”—literally “have you eaten?”, the traditional Tâi-gí greeting. Children, unburdened by preconceived notions, tend to absorb the phrase by rote. But adults might pause and ask, “Shouldn’t it be lí hó?”—reflecting the influence of Mandarin, where that’s the default greeting. That’s a perfect moment for the teacher to explain cultural nuance in Tâi-gí speaking context, or supplement with related expressions.

Koh, chhin-chhiūⁿ Tē 11 khò, ū “khòaⁿ–khí-lâi” kap “phīⁿ tio̍h” chi̍t 2 kù. Gín-á kiám-chhái tō o̍h–khí-lâi, goán mā bô ké-soeh in ê cheng-chha. Tōa-lâng tiāⁿ-tio̍h ē mn̄g, siáⁿ-mih to͘-ha̍p beh kóng “–khí-lâi,” siáⁿ-mih to͘-ha̍p beh kóng “tio̍h.” Sian-siⁿ mā thang ké-soeh kàu bêng-pe̍k.

Another example comes in Lesson 11, where we teach two expressions: “khòaⁿ–khí-lâi” (literally “when looked upon”; roughly “it appears”) and “phīⁿ tio̍h” (literally “smells like”). Children will likely pick them up by example and context. And indeed we did not explain further in the book. Adults, on the other hand, will ask: when should I use –khí-lâi versus tio̍h? These questions create great opportunities for deeper discussion.

Chóng-kóng, ū kā iù-lō͘ ê pō͘-hūn chhàng tī chheh–ni̍h. Gín-á ti̍t-chiap kì–khì-lâi, tōa-lâng thang jīn-chin khì khe-khó.

Throughout this book, we’ve intentionally embedded moments like these—linguistic and cultural nuances waiting to be discovered. For kids, the learning process is intuitive and experiential. For adults, it can be analytical and reflective. But both paths are valid, and both lead to the same goal: reclaiming and revitalizing Tâi-gí, together.

Q: What do you hope Tâi-gí language learners will do next to cultivate their fluency after going through your book?

A: [Lûi Bêng-hàn] Nā chò pē-bú ê lâng, tio̍h kap gín-á tâng chê ha̍k-si̍p, kā Tâi-gí khioh tńg-lâi chò seng-oa̍h ê chi̍t-pō͘-hūn. Thang chham-khó chheh lāi-té “Chhiâⁿ-ióng Siang-gí Gín-á” ê pō͘-hūn.

Parents should learn and improve their Tâi-gí alongside their children. In doing so, Tâi-gí can once again become a living heritage passed down within the family. For inspiration, take a look at the short piece “Chhiâⁿ-ióng siang-gí gín-á” in our textbook.

Nā sin-oh-soaⁿ, tio̍h ài chham-ka Tâi-gí chū-hōe, ke thiaⁿ, ke kóng, chiah ē chìn-pō͘.

If you’re a beginner, make a habit of attending Taiwanese-speaking gatherings. The more you hear Tâi-gí, the more comfortable you’ll become speaking it. Fluency comes with use.

Chiong-kî-bóe, tio̍h bat-jī, tha̍k chheh, hoat-tián Tâi-gí kóng bān-hāng-mi̍h ê lêng-le̍k.

But don’t stop there. Eventually, you’ll need to become literate in Tâi-gí. Read more. Build the vocabulary and confidence to speak about anything—from everyday life to complex topics—all in Tâi-gí.

M̄-thang iōng Hán-jī o̍h Tâi-gí. M̄-thang iōng Tiōng-kok-ōe o̍h Tâi-gí.

And just as important: avoid the trap of learning Tâi-gí through Chinese characters or Mandarin. These are different languages with different logic. To truly reclaim Tâi-gí, you must approach it on its own terms.

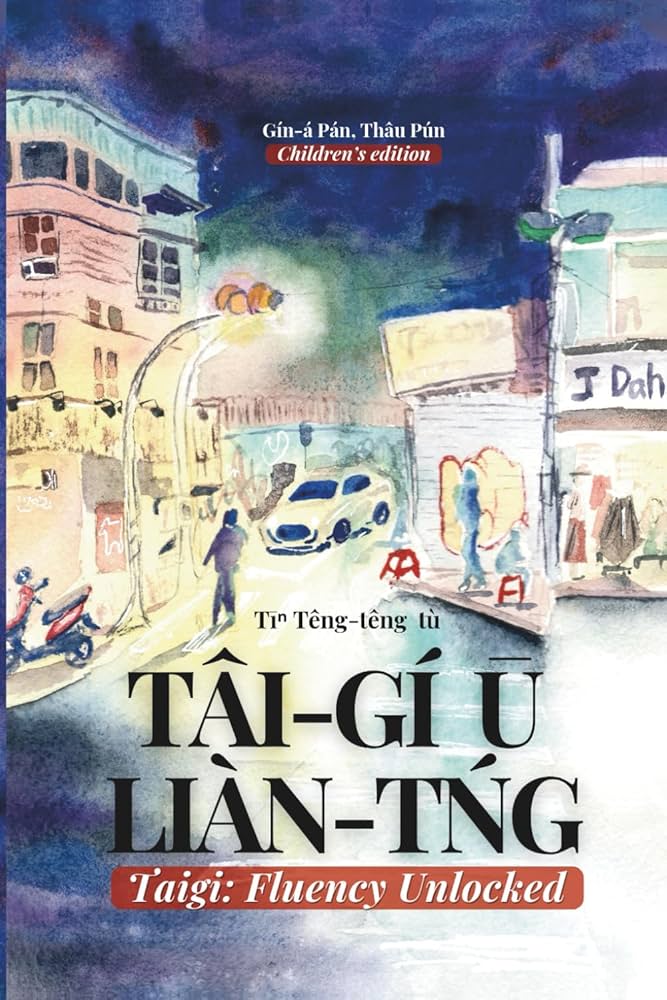

You can find their textbook, “Taigi: Fluency Unlocked: Tâi-gí Ū Liàn-tńg,” here. From the authors:

Children Friendly: We understand that for a language to survive and prosper, it is crucial to nurture the next generation of native users. We made the conscious decision to design the book with a conversation-based, graphic-aided, intuitive learning experience, particularly suitable for preschool audiences, (but equally effective for other age groups and even adults).

Pe̍h-ōe-jī: We cannot stress enough, for a language to assume the role of cultural carrier for a people, the importance of a standardized writing system. We believe that Pe̍h-ōe-jī, a romanized Tâi-gí writing system with a history of being used by Taiwanese for more than 150 years, is the ideal tool for documenting Tâi-gí. An alphabetic, phonemic writing system is easy to learn and helps immensely with pronunciation. The long, native history imparts a sense of tradition and belonging.

English, No Mandarin: We are painfully aware of the overwhelming dominance of the Mandarin language and the Hàn-jī scripts over nowadays Taiwan society and overseas Taiwanese diaspora; in particular, how the dominance dropped such a heavy anchor which always finds its way to disrupt and distort a still reviving Tâi-gí language. To mitigate such toxic influence, we prefer English over Mandarin, when translation or explanatory notes are needed in the book.

Leave a Reply