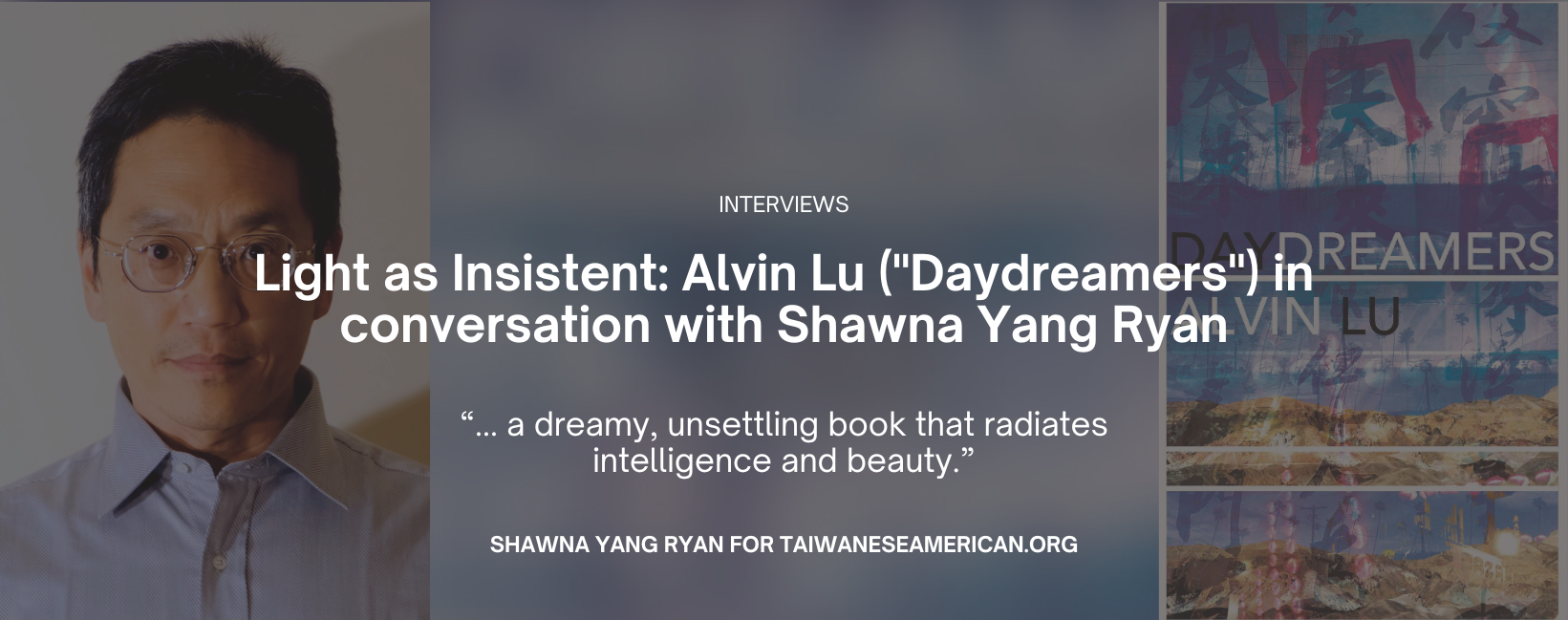

Alvin Lu’s second novel, Daydreamers, was released on July 15th. It’s a dreamy, unsettling book that radiates intelligence and beauty. Difficult to summarize, I will rely on this line from the publisher’s description, though even that cannot capture the many layers of this book: “Cycling between San Francisco, Los Angeles, China, and Taiwan, the novel unfolds across generations of Chinese immigrants and diaspora artists, linked by tenuous friendships, publishing feuds, and the obscure threads of an act of violence.”

Lu’s first novel, The Hell Screens, was set in Taiwan, and its prose–like the narrator’s cloudy contact lenses that give him a view of the spirit world–settled a kind of filter over my experience of the place that has never really lifted, more than twenty years later. In his second novel, he does the same with California. It’s a California I both know, but also don’t know. He brings to the page a landscape that feels so intimate to me as someone who has spent most of her life in California, but he also defamiliarizes it, makes it hazy, almost uncanny. Lu is recognized as an exquisite writer, his work has been called “brilliant,” and the novelist and Brown University professor Carole Maso, herself an exquisite writer, saluted him in an essay thusly: “Alvin Lu: citizen of the universe, the whole world at his fingertips. In love with the blinding light out there, the possibility, world without end, his love of all that is the future.” A New York Times book review compared his work to Nabokov, Borges and Calvino.

Alvin Lu is one of the finest American novelists working today. On the occasion of his second novel, I spoke to him about his work and his process.

Shawna: It was wonderful to be immersed in your world and in your prose again. Though grounded in a familiar, sunlit world, the story is eerie, a bit amorphous. It might be that you capture the feeling of multiple levels of translation very well, a clarity of language, but also a sort of peripheral haziness, as if the reader knows there could be other ways of seeing. In fact, now that I articulate this, I realize this is the exact quality of a daydream. I noted this description as an example of your prose style: “The parking lot was steamy with fog, the light burning softly through it, not that different from up north, but more insistent.” The line is so vivid, complicated through multiple clauses, and then ends in this intangible adjective: “insistent.” Light as insistent. This might be kind of an abstract question, but how do you form your sentences? How do you think you developed your prose rhythms?

Alvin: “Clarity of language, but also a sort of peripheral haziness, as if the reader knows there could be other ways of seeing” is a great way to describe reading a work in translation.

I would keep journals, but ego-free ones, just pages of still lifes made with words. Description gets badmouthed these days, by impatient readers wanting to get on with the story and stylists who privilege voice, but description was how I got serious about this business. I used to be a pretty visually-oriented writer; people liked to use “cinematic” to characterize my stories. You can see this in The Hell Screens, where sense and logic are often missing, but at least there’s an image, or a lot of them. Back then they existed in their own containers or frames. Now, or at least when I was writing Daydreamers, I fuse them together and sand down the joints with the kind of shifts that you notice in that sentence, so a single image might get turned over or repositioned a few times. I probably got this from reading Chinese poetry, but the movies played a part too.

Shawna: Now that you mention it, I can see the influence of Chinese poetry in your imagery and precision. Another thing I was struck by: This is such a California book. Landscapes that don’t usually get literary love—like the dry boring bits of 580—are described with such precision and beauty. Not since Joan Didion has a writer so well captured the feeling of California. What place does California have in your writing overall?

Alvin: I was born, grew up, and continue to live here and, as I mentioned, the material I start with is often observations of my immediate environment. But for a long time I had a fairly serious block writing about California. This will sound ridiculous, but an early draft of The Hell Screens was about psychic kids set in San Jose. I had an idea of starting a new subgenre of science-fiction that took place in Silicon Valley, the way Greg Bear’s Blood Music is about biotech in San Diego, but I couldn’t get it to work. Then I thought of shifting the setting to Taipei and turning all the psychic and science-fiction elements into supernatural ones. For whatever reasons, besides the obvious one of abandoning the original ludicrous premise, once I did that, it all fell into place.

Part of it was that I had a hard time describing San Jose. Even though I was intimately familiar with the suburban Bay Area, it was hard as a young writer to convince myself it was interesting. But Taipei is full of incident and visually rich and even though I knew it well, it was still exotic enough to ignite the fascination I needed to write about it.

But of course California is full of its own mythology too, and by the time I was working on Daydreamers I was confident I could find what was in those “dry boring bits.” Some time spent in Japan also helped me see it with new eyes. In the novel it’s being viewed from second-generation, first-generation, and new immigrant perspectives.

Shawna: Yes! That’s it–it’s that we see California though this shifting, kaleidoscopic perspective.

You are writing about writers in this book, and the metacommentary on writing is another interesting aspect. I was struck by the searing comment on writing in America: “By the time I got to America, everything I just said about writing became the reverse. Here, one must keep moving all the time. This suits me better personally, but writing here is stasis. The consequences of it are easy to predict: there are none.” To me, this reads as a critique that, in America, writing does not change lives or worlds, that literature is inconsequential. What are you trying to say through Daydreamers about the value of literature across different cultures?

Alvin: Stacey Levine observed that the subplot about the Society was funny, even though everyone in the novel takes it seriously, and maybe we’re supposed to take it seriously too. Which is exactly right: the whole enterprise is pathetic, they aren’t producing anything of value as far as we can tell, but it is all they have. And they have something back of them, which is the knowledge that all this had value somewhere else, even if that place doesn’t exist anymore. By the time it gets to the narrator’s generation, he doesn’t even have that. I’m not sure if I answered the question, but I’m trying to say culture, literature, and value are imaginary, which is fairly obvious and not the same as nothing.

Shawna: I am going to have to ponder that a bit. Speaking of “societies” of writers, when you and I began our writing journeys, in the 90s, there were not a lot of Asian American role models, and I can’t think of any Taiwanese American writers publishing at that time (in fact, you were my role model because your novel The Hell Screens was the first American novel I’d ever encountered set in Taiwan). When did you realize you wanted to write? Who were your role models? Did you consider it a career path, and if so, how did your parents respond?

Alvin: I don’t think anthologies that seemed to hold a key for me, like The Portable Lower East Side’s “New Asia” issue, Charlie Chan Is Dead, and Premonitions, or novels like Dogeaters, Bone, and Memories of My Ghost Brother, provided role models so much as they suggested practicable directions. It was a literature of possibility. Everything else seemed kind of burdened. I remember a college friend waving around a copy of Dictee. None of us had heard of it before. It was the wildest thing, trying to figure out what to do with that. But something I’ve mentioned to a couple of Asian American writers who came on the scene at that time—Karen Tei Yamashita and Walter Lew—and one who came after—Eugene Lim—is that 1995 once seemed like a new beginning for Asian American writing, or at least an innovative strain of it, but really it was a sort of ending.

My first-gen parents responded to my writing the way you might expect, but I did not necessarily disagree with them. There have been people along the way, who I respected and worked in publishing and as writers, who quite reasonably warned me off this life. I have been pretty ambivalent about the whole business, to be honest. Publishing has been incidental. It’s never been a career for me, but maybe I got lucky that way.

Daydreamers can be purchased here.

Alvin Lu will be reading on August 14 in Seattle at Elliott Bay Book Company and on September 17 in San Francisco at City Lights Bookstore.

Alvin Lu lives in San Francisco. He is the author of the novels Daydreamers and The Hell Screens.

He is an MFA recipient from Brown University, winner of the John Williams Prize for Prose, and judge for the 2026 Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize. Recently he was guest Prose Editor of the literary magazine Your Impossible Voice. Other writings have appeared in 3:AM Magazine, Denver Quarterly, The Dodge, Evergreen Review, Firmament, minor literature[s], new_sinews, Rain Taxi, ZYZZYVA, and the Akashic Books anthology San Francisco Noir.

Shawna Yang Ryan is a former Fulbright scholar and the author of Water Ghosts (Penguin Press 2009) and Green Island (Knopf 2016). She was formerly the Director of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa. Her writing has appeared in ZYZZYVA, The Asian American Literary Review, The Rumpus, Lithub, and The Washington Post. Her work has received the Association for Asian American Studies Best Book Award in Creative Writing, the Elliot Cades Emerging Writer award, and an American Book Award.

Leave a Reply