This essay was originally written for my personal newsletter, but I hope its reflections on heritage, human rights, and ethical imagination may resonate with the broader Taiwanese American community. 🫶

Hello from Taipei, where I’ve collected so many museum pamphlets and cute paraphernalia that I am tempted to start a junk journal (though now that I think about it, this Substack is an intellectual junk journal of sorts). I’m so grateful to have also spent time this week with people I’ve long admired (even meeting some IRL for the first time)!

Last night, my mom hosted a wonderfully eclectic dinner party. Among the guests were activist-sociologist Professor Shu Wei-der (許維德), whose research has focused on Taiwanese Independence Movement activists in the United States, and activist-historian Professor Hsueh Hua-yuan (薛化元), who has chaired the February 28 Incident Memorial Foundation, among other prolific appointments to many of Taiwan’s most esteemed institutions.

I am so self-conscious about the arrogance of my effusive name-dropping. But what I’m really trying to express is that throughout my life, I’ve had extraordinary proximity to changemakers. And that proximity has given me evidence, from a very young age, that change is possible and each of us is responsible for doing our part. This has been the foundation for all the hope I have in community organizing, and the core of what makes my heritage special to me.

This reasoning had come up in a conversation earlier this week at Daybreak too (where I met other role models of mine!), when we were talking about where our hope comes from—or whether it’s even necessary to sustain the work each of us does. And once more, when I was yapping with my longtime friend for a TaiwanPlus segment about Taiwanese American identity. I’d shared that being raised by activist-elders, seeing their legacies and contradictions up close, has given me faith in the capacity of imperfect human beings to still achieve something profoundly good over the arc of their lives.

I thought of this again today while visiting the National Museum of Human Rights. While chatting with the auntie at the front desk, I mentioned that I’d come because this history felt personal to me, embodied in the people I’ve met, among the more prominent: Yao Chia-wen, Lu Hsiu-lien, and Chen Chu— heavyweight names whose presence, however brief, in my life and community has been a reminder that courage is a human choice and transformation, a human construction.

Because I have known and loved complicated people of consequence, I believe in each of our capacities to lead ethical lives of consequence (and in the grace due to each of us when we falter along the way). Because I have known people who galvanized their communities, I believe in our duty to be deeply involved in the places we call home and the spaces we build. When I speak about my fervent desire for young Taiwanese Americans to locate themselves in history, this is what I mean: for us to claim our agency, to move through this world knowing we belong to it and it to us, and to feel passionately that we can—and must—in our own way make it more beautiful, more generous, more loving.

All that to say – forgive me when I name drop. I’m just so grateful that this has been my life (and anxious that I am not stewarding it well enough).

But what I wanted to write about was the museum!

This was the fourth of my museum visits this trip, after the National Museum of Taiwan History (Tainan), National Museum of Taiwan Literature (Tainan), and the National 228 Memorial Museum (Taipei).

The Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park is one of three spaces for the National Human Rights Museum. I’ve referenced their digital archives, in particular their oral history series, for some time now as I’ve been drafting the relevant chapters of my novel (spoiler alert – kind of?).

Suggested reading: Enbion Micah Aan has an excellent and more comprehensive overview of the museum here, with lovely photographs, for No Man Is an Island.

The one I visited (Jing-Mei) is located on the grounds of the former Detention Center, where political prisoners were once held and interrogated during Taiwan’s White Terror. Its deliberate preservation — the cells left intact, some original buildings still standing — creates a surreal environment for the ghosts that inhabited them to speak to and with those who have come looking for them. I felt, walking through the barracks especially, that the hardest contradiction of justice is not between pain and possibility, but that many who paid the price for it were never given a choice.

I learned, for example, that those without descendants have been locked behind a kind of proxy censorship, their files withheld under privacy laws, and thus their stories kept behind bureaucratic lockdown. But if there is no one left to look for them, how will we ever know who they were and what they wanted?

But more viscerally, I felt a deep perplexity as a Taiwanese American—moving through a Taiwan that has made public its reckoning with state violence, while coming from a United States that cloaks its own in the language of liberty and human rights. This had chewed at me, too, at the National 228 Memorial Museum, where one exhibit (“Silenced Pages” 禁書時代) laments literary censorship as a frightening relic of Taiwan’s authoritarian past. Furiously, I’d scribbled on the sticky note provided for reflection: “Nearly 4,000 books were banned in the United States last year, including picture books for children!” And then I sort of hid it behind another stack of notes, because I did not quite know how to feel about this admission.

At the beginning of my Jing-Mei tour, I cried very, very, very ugly, snotty tears at the VR screening of “The Man Who Couldn’t Leave” (which is excellently and tastefully done, I highly recommend booking it and having tissues ready in your fists).

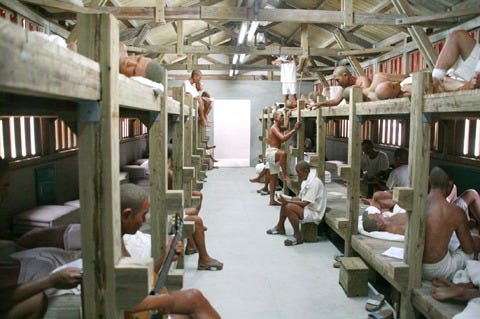

The film introduces former political detainee A-Kuen, who narrates his experiences on Green Island as his older self. Around him are the wooden barrack beds, with bodies pressed so closely together that no one can stretch comfortably. We see the unbearably stuffy, unhygienic rooms that stripped detainees of even the most basic privacy and dignity. Because he recounts these events in hindsight, the story is framed as “recent history”—a warning, a lesson: detention like this belongs to the past, and we must learn from it to prevent its horrors from repeating.

And yet — I am American.

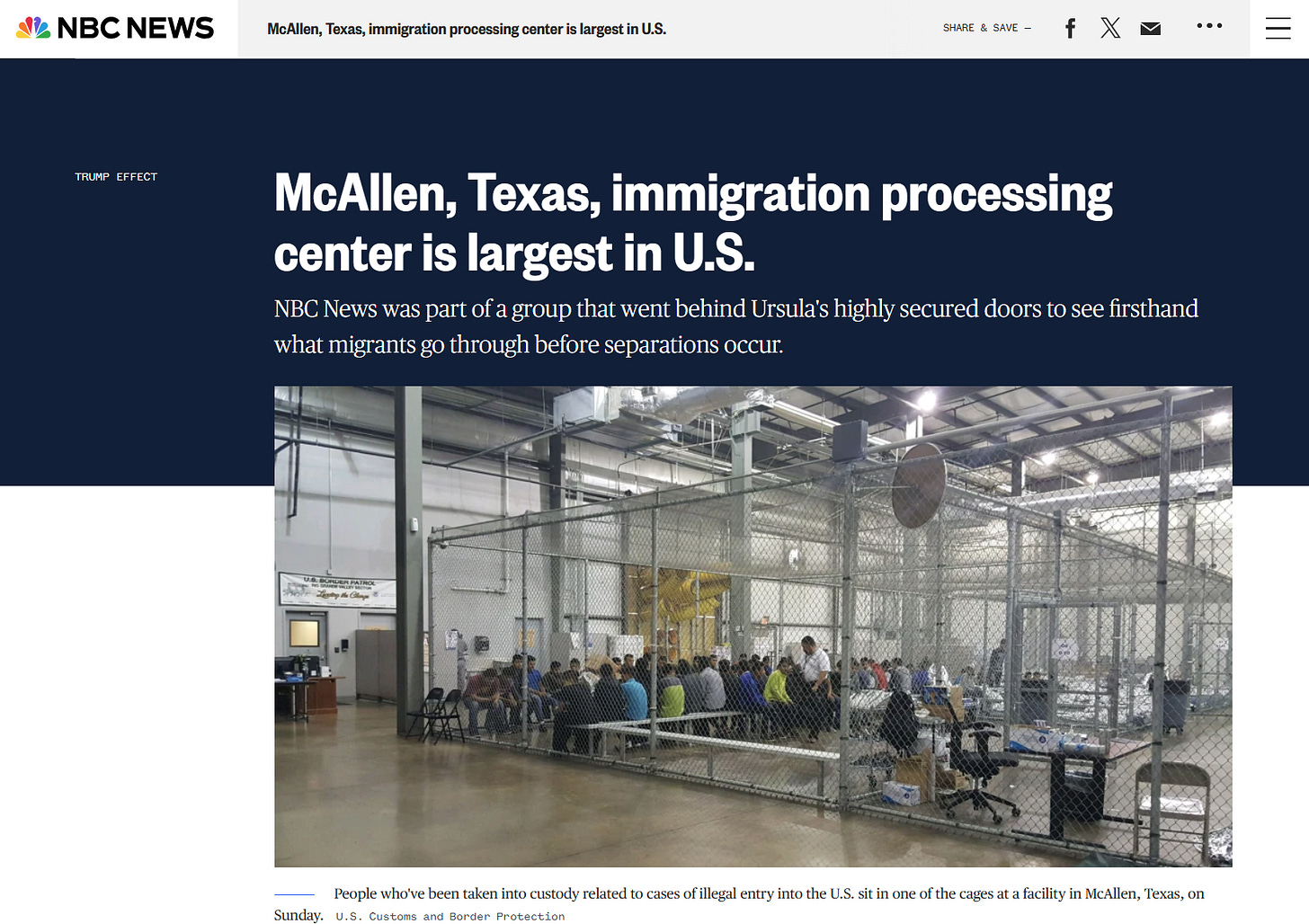

In the United States, we rarely think of ourselves as the jailer, though we operate from an astoundingly carceral logic. Across the country, young people are surveilled and criminalized for speaking out on college campuses; families are violently separated and detained indefinitely in ICE facilities, and some are deported to countries where they know no one and to which they have no connection; entire communities live constrained by punitive systems that claim to protect us while brashly eroding our freedoms. The walls and political symbols in the United States may look different, and the language may be sanitized and baptized, but the underlying architecture – restricting movement, policing thought, normalizing fear and division, pitting neighbor against neighbor, it is the same and it is here, now.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that Taiwan has fully completed the work of transitional justice, nor that America is the only nation undergoing democratic backslide; or comparing the two nations to rank one as “better” than the other. Rather, I’m trying to do what I learned at NATSA this year—to relate rather than compare: to connect the aspirations of people in both places—the hope for dignity, safety, and accountability—and to observe how grief is expressed when we fail, as well as how progress becomes possible when we collectively choose, every day, to try to do better… to see what each society might learn from the other about how memory is weaponized, and how it might instead be made humane.

When I walk through Taiwan’s museums, I think of historian Yi-Ting Chung’s reminder that every archive is a site of power and privilege, and every artifact produced under asymmetric conditions of accessibility and legitimacy. And of Kirk A. Denton’s observation in The Landscape of Historical Memory1 that museums in post–martial-law Taiwan are not neutral repositories of the past but active sites where party politics, identity formation, and nation-making collide. They display not simply what a nation remembers, but what it is willing to admit – leaving out what it still cannot bear to face and who it deems unworthy.

With insider administrative lore from Professor Hsueh (and the Trump administration’s starvation of libraries and museums), we also remember these institutions are inevitably arenas for partisan struggle, beholden to human leadership and funding, to political tides that can shift towards confession (rarely) or vindication (more often). Museums are fragile precisely because memory is fragile; they survive only as long as people believe that history is worth telling honestly, and are given the resources to do so.

Furthermore, in How the Word Is Passed, American writer and poet Clint Smith describes visiting monuments and landmarks that tell the story—some honestly, many deceptively—of how slavery shaped the United States. “It is not enough,” he writes, “to celebrate singular moments of our past or to lift up the legacy of victories that have been won without understanding the effects of those victories—and those losses—on the world around us today.”

His reflection resonated with me as I moved through sites like Jing-Mei: the recognition that truth-telling, when institutionalized, risks calcifying into ritual unless we accept the responsibility of its teachings, and the staggering but critical task of applying the lessons we have learned to people who do not look, talk, or think like us.

For those of us who feel intimately affected by the histories these museums span, our task is not only to bear witness but to respond—to become capable of the moral imagination that can alchemize memory into action. Our sympathy for “prisoners of conscience” can be tugged at the seams to reveal a broader curiosity about what justice might look like without cages, and what repair is possible if we prioritize care and dignity over punishment. If we can mourn those who were detained for their beliefs, perhaps we can also begin to question why our societies continue to accept detention as a condition of governance. The same moral imagination that grieves wrongful imprisonment must also be capable of recognizing that suffering does not become just simply because it is legalized or bureaucratized. What if abolition, then, is not a radical rejection of order but an insistence on the possibility of transformation—on the belief that people, and nations, can change when given the chance to do so with care rather than coercion? (Michelle Kuo articulates this more beautifully here).

What if our ancestors are looking at us from their museumified prison cells, begging us from their engravings on memorials and monuments, ghost to able descendant: stop building cages.

As a Taiwanese American, I find it unconscionable to recognize the cruelty of solitary confinement on Green Island, yet look away from the cruelty of indefinite detention in ICE facilities, or the desolation of American jails filled with those too poor to afford bail. To grieve one without interrogating the other is to make a callous indictment for who deserves freedom and who does not, to become people willing to deny to others what we believe is sacred for ourselves.

My hope is twofold: I wish for my Taiwanese American elders to see their own struggles reflected in this generation of abolitionists and activists fighting for Black American reparations and against ICE detention, police brutality, environmental destruction, and the ongoing genocide of the Palestinians; who are not “soft” or “misguided” but instead kindred spirits who too have only ever wanted for ordinary people to have dignity and safety. I wish for my Taiwanese American peers to find ourselves doubly stirred towards solidarity with the most vulnerable.

And I draw so much inspiration from the ongoing work of historians, organizers, artists, and everyday people in Taiwan to make sense of of their/our inherited contradictions of heritage, memory, and identity – and to do so while avoiding “avoid both destructive or commodifying forces.”2

The inscription on the back of my Jing-Mei museum guide reads: “Only by remembering the past can we ensure it will no longer happen again.” I trust that this sentiment is echoed in countless other institutions, memorials, and museums. And yet such things – war, genocide, human rights abuses, censorship – are happening again.

The inscription assumes that memory is enough, but memory without imagination leaves us exactly here. So what can we salvage from such despair?

We can allow memory to instruct our behavior—to change how we treat others, how we build systems, how we define safety. Remembrance is only ever liberating when it changes the living. And thus I believe: we build museums so that one day, we can stop building cages.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Leave a Reply