As we celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, TaiwaneseAmerican.org is pleased to continue with our series of interviews highlighting some accomplished community members who have pursued interesting paths in their professional careers or personal projects. We launched these interviews during Taiwanese American Heritage Week, and we’ve selected these individuals particularly because their stories include how a Taiwanese American community organization or experience has shaped their experience or life path.

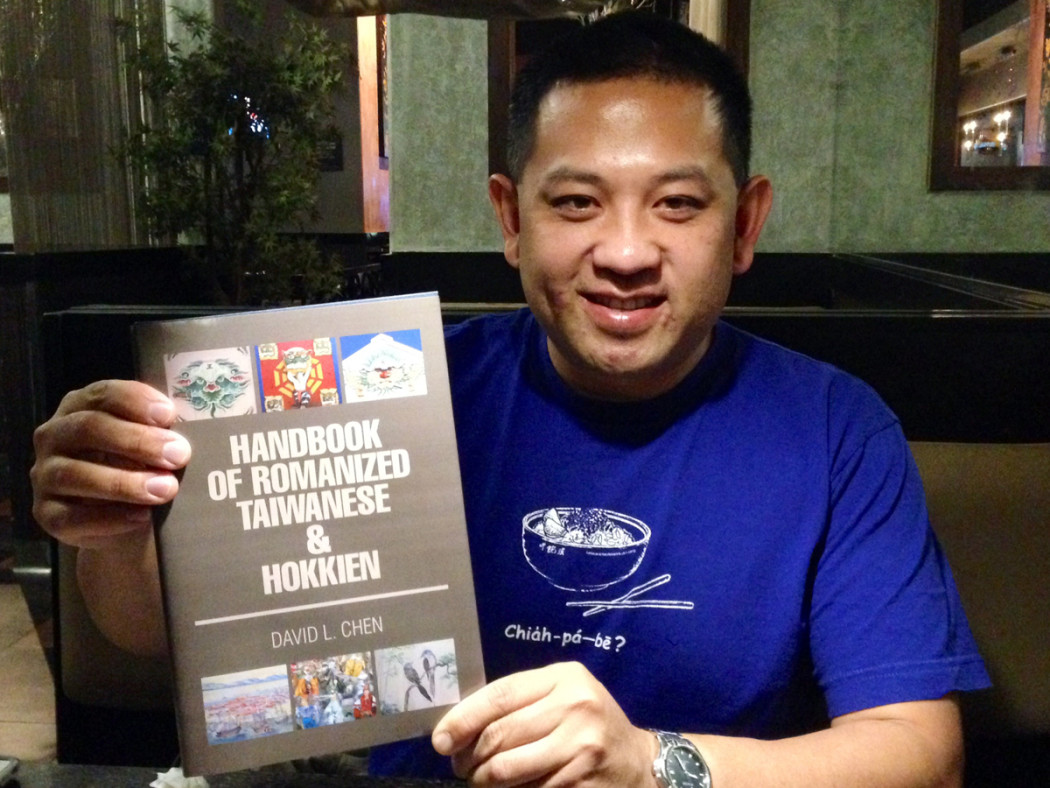

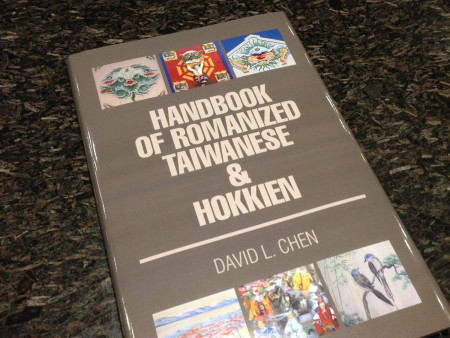

In this interview, we present David Li-Wei Chen, the author of a new text titled Handbook of Romanized Taiwanese & Hokkien that helps guide people in learning the Taiwanese language. TaiwaneseAmerican.org’s HoChie Tsai recently met up with David and chatted over some Taiwanese dinner to discuss his motivation for producing this resource.

HoChie: Hi David! What a wonderful mission you’re on helping to preserve and teach the Taiwanese language! Tell us a little bit about yourself and background.

David: Well, I was born in Taipei and immigrated with my family to Seattle, Washington in the mid 1970s when I was almost two years old. I am the oldest of two, and my brother was born in Seattle. I attended the University of Washington where I studied and majored in Civil Engineering. I later moved to Orange County, California to obtain my Masters in Civil/Transportation Engineering at University of California, Irvine. I currently work and reside in Orange County. I have been largely active in the Taiwanese community or through my church because both have been pretty consistent in my life back in Seattle. I continue those activities when I moved to California.

H: What inspired you to create this text to help teach Taiwanese romanization and pronunciation?

D: I believe I owe most of the inspiration to the music I have been exposed to, and my bilingual / bicultural upbringing. My first foreign language class was actually Taiwanese, but it lasted less than a year as the teacher moved away. A few years later, I took weekend Mandarin classes where I learned Mandarin, Zhuyin (bopomofo), and how to write traditional Chinese characters. I studied three years of Japanese in high school and learned hiragana, katakana, romaji, and Japanese kanji characters. During my time at UCI, I was able to take two quarters of Mandarin with Pinyin. So, by the time I finished my Master’s degree at UCI, I had already been exposed to characters, phonetic symbols, romanization, and tones… all elements of East Asian languages.

My high school Japanese teacher, influenced and inspired me the most to develop materials to teach Taiwanese. In learning Japanese, you are forced to address all the elements–romanization and spelling, phonetic symbols, tones, and characters. Although in Mandarin and Taiwanese, most writing is in traditional Chinese characters, the ability to grasp all elements of spoken language are important… especially when using dictionaries.

H: And, what about this musical inspiration that you mention?

D: The musical component was being exposed to Japanese enka music records that my parents had and that I used to sing to when I was a child. Also, I started enjoying Taiwanese church hymns and folk songs. I also used to listen to songs in Mandarin by Tsai Chin and Teresa Teng while in the car on frequent road trips. In my college days, I was active in the Taiwanese Student Association, and many of my friends loved to go to karaoke, and that’s where I got to learn more cool Mandarin and popular Taiwanese songs. I am used to picking up songs in other languages and, to this day, I transcribe and romanize many songs.

H: It seems so few young people speak Taiwanese in Taiwan these days. What are your thoughts about preservation of culture and identity through language?

D: Due to Taiwan’s history of foreign occupation by the Japanese, then the Nationalist Chinese, the Taiwanese language and pop culture always took a step back to Japanese, and later, Mandarin. Education in Taiwan has always been in a language other than Taiwanese. Also, I believe the Taiwanese language and culture were largely suppressed during the period of martial law. This left a legacy of largely Mandarin education and Chinese history. So, a Taiwanese Mandarin-based mainstream popular culture–music and television media–has developed and has heavily influenced the Taiwanese people.

I would say that Taiwanese language-based television and television media has progressed somewhat since the lifting of Martial law in 1987. Back in 1990, I remember seeing commercials, TV shows, and TV news, broadcasts in Taiwanese. However, the development of Taiwanese language-based television music and television media was largely on hiatus. Now, what I have seen in the past 10-15 years, is the development and cultivation of a Taiwanese Language-based popular culture through music and television media. We see more native languages curriculum in schools (Taiwanese, Hakka, Indigenous Formosan languages) and public announcements on airlines and train stations in Taiwanese and Hakka, for example. Singer Jody Chiang (also known as Chiang Hui 江蕙) has been famous for her Taiwanese ballads since 1980, but did not hold her first concert in public until 2008. I also think that today’s technology has allowed Taiwanese language music and media to become more mainstream and easily accessible.

H: Yes, I agree, and have noticed the changes in Taiwan, too. How about us here in America, though? What are your thoughts about 2nd generation Taiwanese Americans in terms of Taiwanese language or identity preservation?

D: Many of us Generation X and Millennials associate Taiwanese language largely as a language that we speak “at home” with our grandparents and parents, but not with friends or in public. This is tough to change. Because of this, many young people are so used to communicating in mainstream Mandarin to each other, so Mandarin is passed down to the next generation instead of Taiwanese.

In growing up in the United States, I believe most of us did not fully understand the politics of Taiwan regardless of how much our parents told us or did not tell us. However, our identity was largely fostered by the languages spoken at home or between our parents and their friends. My parents spoke largely Taiwanese, so I knew we were Taiwanese. It was the easiest and most natural thing to do. However, nowadays, I do notice that Taiwanese language and culture do not get passed down from the Taiwanese parent. What usually happens is that Mandarin Chinese culture gets passed down. As long as Mandarin stays very dominant, our culture gets watered down. This is not just happening in the US, but for many overseas Taiwanese communities as well.

When Taiwanese language ceases to be spoken or to be relevant to overseas Taiwanese communities, our communities overseas may cease to exist. It would be sad if we as Taiwanese Americans are unable to pass down Taiwanese cultural legacies to the next generation. Language, music, and cooking are the easiest items to pass down to the next generation. It would be cool if the next generation could identify what Taiwanese culture is since it sometimes seems ambiguous or obscure. The question always comes up, “Isn’t Taiwanese Chinese?” For those of us who have full or partial Taiwanese ancestry/blood, we need to be able to answer this.

H: Tell us more about this textbook you have authored. What makes it different from other resources available out there?

H: Tell us more about this textbook you have authored. What makes it different from other resources available out there?

D: I wrote the Handbook of Romanized Taiwanese & Hokkien based off my familiarity with foreign language resources that are available for Mandarin and for Japanese. I wanted to better my Taiwanese speaking ability but found a serious lack of Taiwanese/English materials that were in-print or available. Most of my resources were second-hand, out-of-print, and expensive. Most also assume you know how to read and pronounce Taiwanese Romanization, or else they say in a statement that you need a Taiwanese or Hokkien language instructor, which we know are far and few between. Most Taiwanese language materials available are largely for Mandarin and Japanese speakers in Taiwan and Japan, and require literacy in Mandarin or Japanese. The Taiwanese language teacher at Taiwan Center of Greater Los Angeles, writes a lot of traditional Chinese characters and communicates/explains largely in Mandarin, not English. This is problematic because more than half of the overseas Taiwanese, including Taiwanese Americans, will not know any Mandarin or how to read/write traditional Chinese characters unless they speak it at home, or they attend weekend Mandarin Chinese language schools.

The Handbook of Romanized Taiwanese & Hokkien introduces up to five Taiwanese Romanization methods with the emphasis on Pehoeji or Church Romanization, which is the most common. I cross-reference each Romanization method with Taiwanese Phonetic Symbols (similar to Bopomofo but with more symbols for the Taiwanese/Hokkien language). I also discuss the 8 tones in Taiwanese and tone changing rules known as tone sandhi. I also provide the reader information on valuable resources such as dictionaries and Taiwanese language keyboards that are available on smartphones or on your personal computer. Due to the complexity of Taiwanese Romanization, I felt a book must be devoted to cover the fundamentals of Romanization and Tones alone.

H: What is your hope and plan for this project?

D: I would like to recruit more Taiwanese Americans–especially those who speak Taiwanese well or are motivated in learning how to read and write Taiwanese Romanization–to build a network so that we can create more language materials for our Taiwanese American community. Most Chinese language resources available are for Mandarin and Cantonese. Little is available for anything else. I would like to one day create a some sort of audio files series or a CD companion to my book as well as resources online that are accessible to our Taiwanese community similar to what the younger Teochew Chinese American people do on their website. The Teochew or Chaozhou people are a group of Chinese whose ancestors live in Eastern Guangdong Province, China who have a large overseas population in Southeast Asia and speak a distinct language similar to Taiwanese in terms of grammar and tonality. I am inspired by the Teochew community in their passion to pass on the legacy of their language and culture with English-friendly media.

I think it is up to us to continue our own legacy. Our parents and those prior to us, did not have systems implemented for teaching the Taiwanese language because they too were busy raising us and “surviving” in America. My goal is to encourage the teaching of Taiwanese and for Taiwanese Americans to consider the advantages of writing Taiwanese using Taiwanese Romanization.

H: Tell us about any Taiwanese American community organization that played a role in your identity and growth.

D: I would credit the Taiwan Center of Greater Los Angeles, and Team Taiwan Dragonboat–it’sthe dragonboat team that I paddle with year-round. I must not also forget to credit the Taiwanese Association of Greater Seattle, University of Washington Taiwanese Student Association, and my church community at Seattle Formosan Christian Church. These organizations and resources are very valuable.

H: What’s the best way for people to get a hold of a copy of this textbook? And how is it best used?

D: The website for my book is www.taiwanesehandbook.com where you can purchase it directly from Exlibris, my publisher’s website. It is also available online at Amazon and Barnes and Noble. I also have hardcover and softcover books available at a discounted price. People can contact me directly through my Taiwanese/English Facebook page: David Lip-Ui Tan, or contact me via email at taiwaneseromanization@gmail.com. Also, I host a free session (in Southern California) on how to use this book. I do one-on-one tutoring, but prefer leading small-to-medium size groups.

H: So, out of curiosity, what are your favorite Taiwanese foods? (And can you show me the romanization for those?)

D:

iû-pn̄g 油飯 Taiwanese oily, sticky rice

ló-bah pn̄g 滷肉飯 miced pork, rice

ló nn̄g 滷卵 marinated egg

pâi-kut pn̄g 排骨飯 pork chop rice

chhá bí-hún 炒米粉 Taiwanese fried rice noodle

bí-ko 米糕 sticky rice “cake”

lūn-piáⁿ 潤餅 lumpia, Taiwanese burrito, Taiwanese springroll

sián-chháu tê 仙草茶 grass jelly tea/drink

tang-koe tê 冬瓜茶 wintermelon tea

H: It’s so great that you’re helping to take steps to preserve the Taiwanese language. You’re definitely a great resource to have, and I hope more people connect with you through this endeavor. Thanks so much for your time today!

D: My pleasure, anytime.

LINKS:

http://www.taiwanesehandbook.com

Facebook: David Lip-Ui Tan

Facebook: Taiwanese Speakers Group Global

Facebook: Save Hokkien Language: Speak it with Your Children!

Facebook: Writing Systems for Taiwanese: POJ and Tai-uan Lo-ma-ji (Tai-lo)

Email: taiwaneseromanization@gmail.com

Thank you for doing this interview and helping to bring together the language community of Taiwanese Americans. I definitely will be purchasing this book in the near future and I cannot believe that God answers prayers like this when I feel like it’s been a language that has been suppressed in my own life. I remember when I went to an Asian Pacific conference with Intervarsity, there was a leader that was praying for me and she told me that God would bring a type of translator/translation (?) for Taiwanese into my life, I think this book is the first step towards that prayer being fulfilled and also living with my Ama, over the summer as well.

Esther, thank you. Please contact me if you are interested in more resources. Sincerely, David